Dutch growers were paying around €0.20/m3 for natural gas for a long time. That is, until April 2021. Then the gas price started to rise, at first tentatively and almost unobserved. But, in September, alarm bells began sounding everywhere. A gas crisis and, therefore, an energy crisis had begun. That raised questions. How could it have come to this? And perhaps more importantly for growers whose energy bills are skyrocketing, what now?

Gas meter

A bit of history

To answer these questions, we need to travel back in time to 1959, when natural gas was first unearthed in the province of Groningen. The gas bubble on which Dutch people live expanded over the years. The Netherlands soon began earning a fortune, especially when, in the 1960s, it began supplying gas to other countries. In 1964, Germany was the first country to receive low-calorific Groningen natural gas. Other countries soon followed, as did supply contracts.

It seems trading in gas is lucrative. So lucrative that, thanks to its acclaimed commercial spirit, the Netherlands began buying and reselling this fossil energy source too. Just as the Netherlands has always been a major transit country for fruit and vegetables, so it is for gas. Here, however, the country does not make money from tomatoes and 'moving boxes around' but from gas. By trading in its own and other nations' gas, the Netherlands wanted to ensure that, should the gas under Groningen ever run out, it could maintain its strong position as a gas trader.

Gas being extracted from Groningen's gas field

In 2002, it signed an important deal with Russia, as seen in the short 'Andere Tijden' TV documentary. This documentary includes a clip from the Dutch national Broadcaster, NOS News, showing the then Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende and Russian President Vladimir Putin. They agreed on a 20-year contract between the Dutch gas company Gasunie and Russia's Gazprom. The Netherlands was to buy 'cheap' Russian gas. And Russia, by supplying gas in the summer, could make good use of its transport systems when gas demand is generally low. So, a win-win situation.

What causes the current crisis?

A 20-year contract with Russia. That provides security, no? Yes, until it expires, which it now has. The agreement will have to be renegotiated if the Netherlands wants Russian gas again. That has not happened yet. There have been no news clips of the current Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, shaking hands with Putin, who is still Russia's president. These are sensitive matters. And, these two countries' political relations are no longer what they were in 2002. Russia is using its gas as a political weapon.

The 'Andere Tijden' documentary shows another NOS news segment in which a Gazprom director shows how he can stop the gas supply by the mere turn of a tap. The Netherlands has no influence over this state-owned company's director, but Putin certainly does. In recent months, fingers have, thus, been pointed eagerly in his direction, even though the Netherlands also gets gas from other countries like Norway and the United States.

But, the blame for this crisis cannot be placed squarely on Putin or Russia. The Netherlands itself made policy decisions. Dutch organizations such as Glastuinbouw Nederland are now labeling those choices as 'dangerous'. This NGO represents the interests of the vast majority of Dutch greenhouse growers. They are not the only ones that think so either. The policy is receiving criticism from all sides. A crucial political choice made concerns Groningen. Here, 2019 is a key year.

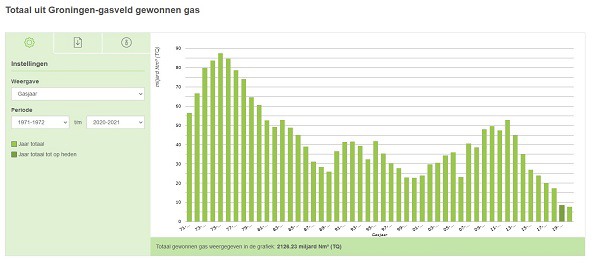

That is when the Netherlands decided to accelerate closing the natural gas tap in Groningen after that region experienced several fracking-related earthquakes. The country was going to stop extracting that gas in 2030. But, due to social pressure, it is bringing that deadline forward. The government promised that production would stop in 2022, which has not yet happened. Now that gas prices are on the rise, there are rumblings that production might even increase again. And Dutch authorities are unwilling to give a new stoppage date.

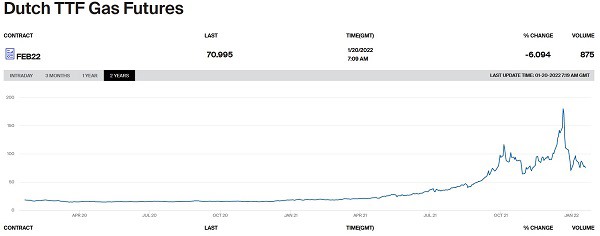

The past two years' gas prices on Title Transfer Facility (TTF), a virtual gas marketplace. Those prices, which had been stable for a long time, began climbing in April 2021. "TTF is the only Dutch (virtual) trading place where our network's gas can be traded. So much of this is traded on the TTF that the platform's gas prices are normative for Europe. The rest of the world also closely follows the TTF's activities," writes the Dutch energy network operator, Gasunie, about the platform on its website.

The past two years' gas prices on Title Transfer Facility (TTF), a virtual gas marketplace. Those prices, which had been stable for a long time, began climbing in April 2021. "TTF is the only Dutch (virtual) trading place where our network's gas can be traded. So much of this is traded on the TTF that the platform's gas prices are normative for Europe. The rest of the world also closely follows the TTF's activities," writes the Dutch energy network operator, Gasunie, about the platform on its website.

In light of the Netherlands' current floundering position, the 2019 announcement is now pertinent. In 2019, an energy specialist responded to the Groningen news in the Dutch greenhouse cultivation platform, Groentennieuws. He stated that "these developments could raise gas prices" and "the Netherlands will have to import more (gas) in the future. The conclusion, even then? "Geopolitical tensions will be of greater importance for the price."

This is now undeniably the case. There seems to be a significant tendency to point the finger at Russia, but let's look further. Other factors, some mentioned in 2019, play a role too. It was said there could be a hold-up in laying pipelines for additional gas supplies. Or the construction of the nitrogen plant in the Netherlands could be delayed. This plant converts high-calorific gas into low-calorific gas. The Netherlands wants to use it to negate the discontinuation of Groningen gas.

As is were, full completion of the plant has been delayed by several months, and construction will take until August 2022. And in Germany, a regulator permit to start delivery via Nordstream 2, a pipeline that brings additional Russian gas to Europe via Germany, has not yet been granted. This might not happen until mid-2022. These are unforeseen circumstances. Still, in practice, large projects are known to be delayed. In this case, though, these delays are 'inconvenient'.

What could be foreseen is the increased gas demand. That could rise, the specialist predicted in Groentennieuws in 2019, because, for instance, natural gas is a less polluting energy source than, say, coal. Dutch growers - to stay with greenhouse horticulture - had switched from burning coal and oil to natural gas as far back as the mid-1900's when natural gas was discovered in the country.

They reduce their electricity usage and CO2 emissions by using cogeneration technology. This method is, however, still far from widespread. Overseas, in Germany, for example, using this technology is boosted by subsidies. The Netherlands supplies gas to Germany and has signed long-term supply contracts with neighbors to the east. The Netherlands will be bound by these contracts. Even as the country itself runs the danger of running out of gas.

Meanwhile, greenhouse technology pioneers, among which the Netherlands can be counted, are already encouraging new steps in the energy field through grants. That is so cultivation can become more sustainable as new methods emerge. Think of 'all-electric greenhouses'. However, at present, electricity is expensive, because, for one thing, it is produced in gas power stations. Or because it is subject to taxes like the Storage of Sustainable Energy tax, which Dutch greenhouse growers heavily criticize.

You cannot always generate solar or wind energy, and how safe are nuclear power plants? There are continuing concerns about that. What does all this mean? Well, a lot of gas is still needed. Climate activists might claim: "Perhaps this crisis is necessary for us to become more sustainable; to get rid of the gas." On the other hand, you'll hear, "You can't go green if you're in the red." If the energy crisis persists, will sustainability increase as quickly as its supporters say it needs to?

What are the consequences?

Many growers could not be bothered with, and neither are they dwelling on how this crisis could have happened. Considering the past and learning from it helps you to not make mistakes in the future. But looking to the future is difficult, if not impossible, for growers right now. The here and now are demanding their full attention. Growers are currently trying to save money wherever they can. Gas and electricity are expensive, so greenhouses are (partly) standing empty.

They are postponing planting and (partially) turning their greenhouse lights off. And some growers are switching to less energy-intensive crops or even stopping altogether when it becomes too difficult, financially. Wageningen University & Research estimated that, for 2021, for the average Dutch grower, 26% of their total costs were made up of energy costs. That's a considerable chunk, especially considering other increasing expenses such as labor and materials.

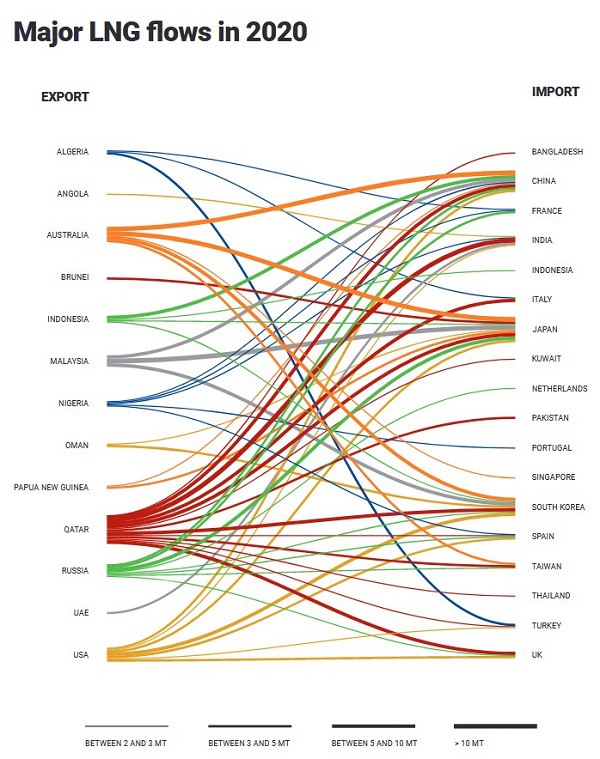

LNG import graph. The International LNG Importers Association's (GIIGNL) 2021 annual report shows 2020's LNG export and import flows.

The current energy crisis will affect each company differently. Those whose energy contracts are on the right side of the line continue farming worry-free. Others are less happy with their gas contracts. Still, more and more growers' contracts will expire sooner or later.

And if the high prices continue, they, too, will have to purchase their energy at grossly inflated prices. Those costs must be passed along, they say; easier said than done. Products dare not become too expensive because if they do, greenhouse tomatoes, for example, run the risk of being exchanged for cheaper, imported ones.

What now?

That is up to President Putin, some say. He has made the Netherlands dependent on Russia. Or has the Netherlands become dependent? Did the country err, for instance, in not building up sufficient gas reserves of 'buffering' gas? Or, is it that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Netherlands has been concerned with all sorts of other things, except keeping its people warm in the winter?

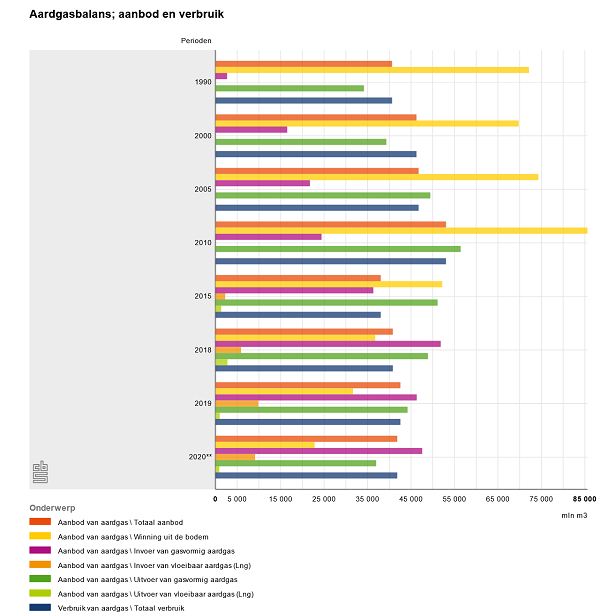

The Netherlands' natural gas balance sheet

The Netherlands' natural gas balance sheet

In the past, the Netherlands deliberately chose to trade in Russian gas. But the Dutch get gas from other countries, such as Norway, or in liquid form (LNG) from the United States, too. Last fall, gas prices were sky-high. Yet as soon as the ships carrying LNG arrived in Europe, those prices fell. Is that what Putin wants? More US gas interference in Europe? And what does the Netherlands, a net gas importer since 2018, want? Or can the Dutch even call the shots anymore? Is it, after years of being a gas powerhouse, at the mercy of the other major gas players?

The brand-new Dutch cabinet had to deal with this tricky situation in its first week, week 2 of 2022, already. Still, is drilling for natural gas for longer and in larger quantities in Groningen really the answer? This does not offer growers any immediate solace, quite aside from this gas not being for their use, but to meet the Netherlands contractual obligations.

Growers are, above all, hoping the cold, harsh weather stays away. That will save a lot on heating. It will also be good for the meager Dutch gas reserves, which threatened to quickly run out when it got cold at the end of last year. A mild winter would provide some relief. The country, nonetheless, has to think hard about the years ahead. High levels of uncertainty and high energy prices every winter certainly are not feasible.

Source: https://anderetijden.nl/programma/1/Andere-Tijden/aflevering/876/De-slag-om-het-gas