Australia is grappling with increasingly extreme and unpredictable weather. In a country where one state can experience widespread flooding while neighbour states endure drought, maintaining sustainable food production is a challenge.

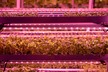

Interest is rising in a farming approach that enhances food security by moving production indoors. Protected cropping is a form of horticulture in which high-value fruits and vegetables, such as berries and capsicum, are produced under optimised growing conditions inside plastic tunnels or high-tech glasshouses.

"By shielding food production from environmental stressors such as drought, flooding, and disease, protected cropping reliably produces a year-round supply of high-quality produce," says Professor Oula Ghannoum, a crop physiologist at Western Sydney University's Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment. "But that dependability brings additional energy and labour requirements," she adds.

Ghannoum is now leading a multidisciplinary research consortium which will boost the industry and upskill workers, to ultimately bolster national food security.

The Australian Research Council Training Centre for Smart and Sustainable Horticulture is a collaboration between Western, The Australian National University, The University of Western Australia, and eight other partners from industry, academia and government.

Between 2025 and 2030, the Centre will train a new generation of tech-savvy horticulturalists, who will undertake research projects co-designed with industry partners to directly address protected cropping's pain points.

"You can train people by sitting them down in a classroom — but I think that a much better, more holistic approach to training is to give students a hands-on research project," Ghannoum says. "By the end of their programme, they will have acquired skills, an understanding of the industry and its challenges, and also the capacity to think critically and problem solve."

The Centre will provide the crucial expertise and people required to drive the protected cropping industry in Australia, says Wayne Ford, CEO of partner Vertical Patch, an organic farm in Smithfield, New South Wales, which uses a form of protected cropping called vertical farming.

"Vertical farming is a high-tech industry and requires highly skilled labourers who are fluent in AI, imaging, and crop biology," Ford says. "We want to see the Centre provide our next research and technical personnel, and our sector's future leaders."

© Western Sydney UniversityLeft to right: Min Gao, Associate Professor Yi Guo, Distinguished Professor Brajesh Singh, Professor Oula Ghannoum, Professor Graciela Metternicht, Shahasad Salam.

© Western Sydney UniversityLeft to right: Min Gao, Associate Professor Yi Guo, Distinguished Professor Brajesh Singh, Professor Oula Ghannoum, Professor Graciela Metternicht, Shahasad Salam.

Deep-rooted sustainability

Baked into the Centre's operations is an overarching emphasis on net-zero solutions and sustainability, says Professor Graciela Metternicht, Dean of the School of Science at Western and a Centre chief investigator. "It's about our children and grandchildren having nutritious food, but still being able to enjoy nature, because the land hasn't been given over to food production", she says.

One branch of the Centre's work, led by Professor Dilupa Nakandala from Western's School of Business, will map protected cropping supply chains and conduct lifecycle analysis on its products, to identify environmental benefits from this mode of food production. "The beauty of enclosed cropping — compared to open field agriculture — is the diverse opportunities to optimise resource efficiency, integrate recycling, minimise waste, introduce circular economic practices and reduce land and water use," Nakandala says.

The Centre's training goals are to teach not only the essentials of protected cropping, but an understanding of the wider social and environmental picture, Metternicht adds. "By embedding this focus into our programmes, we can foster future sector leaders who embrace corporate social responsibility and the principles of circularity and sustainability," she says.

© Western Sydney UniversityDistinguished Professor Brajesh Singh and Min Gao

© Western Sydney UniversityDistinguished Professor Brajesh Singh and Min Gao

A second key focus of the Centre is to develop applied solutions that can be readily adopted by industry, adds Metternicht, who is leading knowledge transfer efforts.

One of the industry's main needs is for research findings to be translated into "something growers can actually use," she says. "We're all about co-designing research projects with industry to make sure the results are relevant and easy for growers and stakeholders to adopt."

Digging in

Research programmes at the Centre are designed in response to industry reports highlighting the sector's challenges and gaps. Ghannoum, for example, is a chief investigator on a project to expand a narrow crop base by integrating high-value crops such as saffron, vanilla, ginger and bush pepper into indoor cropping systems.

Students in this project will compare the health, growth, vigour and crop quality of selected plants. The team will then optimise parameters — including lighting, temperature and nutrient application — to get the best results.

In a parallel project, Professor Zhonghua Chen, plant physiologist and adjunct professor at Western's School of Science, will develop indoor cropping varieties that maintain high yields even under stress.

The focus of his work will be to enhance the tolerance of plants to the stress caused by climate change. By developing varieties that maintain high yields as the temperature climbs, growers can reduce their reliance on energy-intensive cooling in their greenhouses.

© Western Sydney UniversityProfessor Oula Ghannoum and Namal Jayasuriya

© Western Sydney UniversityProfessor Oula Ghannoum and Namal Jayasuriya

The direct impact of high temperatures on cropping is only part of the problem. "The biggest challenge that we face in a warming climate will be pest and disease outbreaks in the cropping facilities," Chen says. As temperatures rise, plants in the greenhouse lose more water into the air through transpiration. The combination of high temperature and high humidity create ideal conditions for many pests and diseases, particularly fungal infections, to spread.

One strategy will be to reestablish some of the stress tolerance and pest resistance lost in modern crop varieties, but still found in their ancestral wild-growing relatives. An alternative approach could be to directly combine the hardiest and the most productive varieties of a crop, by grafting the tough rootstock of the former to the fruitful upper parts of the latter, to create productive and stress-resistant hybrid plants.

Alongside his research, Chen leads the project's industrial engagement component. "Through connections such as internships, our students and postdocs will gain direct experience in applying their findings to benefit the industry," Chen says.

Robots on patrol

A second project co-led by Ghannoum aims to reduce the risk of crops being exposed to pests or diseases. "To minimise infection risk in a protected cropping facility, you don't want people going in and out all the time," she says. As a solution they are developing cameras and sensor technology to monitor crops.

The team will test this technology in fixed locations and mounted on patrolling robots. Ghannoum has also teamed up with Associate Professor Yi Guo, a data scientist from Western's School of Computer, Data and Mathematical Sciences, to develop AI-powered analysis of image and sensor data.

"We want to develop crop-sensing technology to the point that we can monitor each individual plant within the protected cropping facility," Guo says.

Once plant monitoring is automated, the next step is to eliminate the need to send in workers for tedious tasks such as pruning and pest control. "Our ultimate goal is an autonomous robotic platform that not only carries sensors, but has arms equipped with, for example, a sprayer, to very precisely treat an area affected by pests."

Technology is advancing so fast that the team hopes to have a prototype within three years, Guo says.

Across all its work, the Centre is "a place where innovation meets real-world impact," says Metternicht, who highlights its focus on net-zero solutions and circular agronomy.

"These aren't just trendy terms — they're critical changes needed for how we produce food and manage resources," she adds. "It's fantastic to work with people with shared values and aspirations of doing research with purpose."

Source: Western Sydney University