"Systems in controlled-environment agriculture such as vertical farms, algae reactors, or insect farms are already complex to operate on their own," says Jonathan Raecke, PhD Researcher in Automatic Control and System Dynamics at Chemnitz University of Technology. "Once we introduce interconnections, finding truly optimal production conditions becomes a multidimensional, dynamically changing optimization problem."

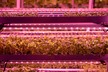

In discussions around controlled-environment agriculture, attention still gravitates toward crops, lighting strategies, or climate recipes, but as production systems grow larger and more interconnected, another constraint is becoming increasingly visible: how these environments are actually controlled. Complexity, in this context, is no longer just biological, but systemic. © Jonathan Raecke

© Jonathan Raecke

A systems perspective from the MELiSSA program

That shift was central to a presentation by Raecke, delivered within the framework of the MELiSSA Space Research Program. Rather than focusing on individual production units, his approach framed indoor food production as a dynamic system shaped by feedback loops, competing objectives, and continuously changing constraints.

"A common misconception is that control engineers believe their models know better than the growers," Raecke adds. "In reality, system constraints and control objectives often come directly from expert knowledge. Our task is to understand what can be modeled reliably and where we need to listen to practical, heuristic expertise. Advanced control works best when practitioners and control engineers work together and combine both perspectives."

Why coupling turns efficiency into a systems problem

That challenge becomes especially clear in multitrophic systems, where plants, insects, algae, fish, and waste streams are intentionally linked. Concepts such as reusing CO2 from insect production to enhance plant growth promise greater efficiency and lower input use. On paper, these couplings look straightforward. In practice, they often expose a gap between theoretical potential and operational reality.

From a systems perspective, the problem is not that circularity fails, but that it is often pursued locally rather than globally. Optimizing one subsystem in isolation can restrict flows or create bottlenecks elsewhere, leaving available resources underused. CO2 may be present within the system, for example, but inaccessible at the moment or in the form plants actually need. What appears efficient at the module level can quietly become wasteful at the system level.

"The first thing that breaks down is efficiency," Raecke said. "Individual production units may still function, but the system rarely performs as well as expected. In multitrophic designs, the goal is to be more resource- or energy-efficient than the sum of the individual systems. Local optimization often prevents that from happening."

From reacting to conditions to predicting outcomes

This is where automatic control and system dynamics enter the picture. Instead of responding to conditions as they occur, Raecke explained that the Chemnitz group develops mathematical models designed to anticipate system behavior and compute operating conditions accordingly. These models form the basis for model predictive control and hierarchical control frameworks that balance multiple objectives simultaneously. "These methods compute mathematically optimal conditions based on the chosen objective function," Raecke said. The objective itself depends on context. "Profitability on Earth and circularity in space."

While those goals sound distinct, Raecke suggested the distance between them may be shrinking. As terrestrial food systems face increasing pressure from water scarcity, energy costs, and resource constraints, challenges once associated primarily with space research are becoming increasingly familiar on Earth. "Given increasing water and resource scarcity," he noted, "the solutions for the two may not be that far apart."

Why this matters beyond research facilities

This convergence between space research and terrestrial food production is beginning to resonate beyond academic settings. It helps explain the growing interest in digital twins, optimization, and advanced control across the vertical farming sector, particularly as operators experiment with more circular and multitrophic designs.

That broader relevance is reflected in the work of Stefan Streif, Professor of Automatic Control and System Dynamics at Chemnitz University of Technology and head of the research group in which Raecke's work is situated. "I was recently appointed a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Association of Vertical Farming due to my expertise in advanced process control, AI, and modelling for IVF/CEA," Streif says.

He has emphasized that while coupled production systems can dramatically improve resource and energy efficiency, they are not inherently stable when implemented in artificial environments. Unlike natural ecosystems, these systems require continuous monitoring, control, and optimization to function reliably at scale.

For more information:

Chemnitz University of Technology

Jonathan Raecke, PhD Researcher

[email protected]

Dr. Stefan Streif, Professor, Automatic Control and System Dynamics

[email protected]

http://www.tu-chemnitz.de/etit/control